Object Oriented C Programming

Purpose

The art of good programming depends upon the discipline of the programmer, no matter what language is being used. The purpose of object oriented programming (OOP) is to produce well designed reusable code. In principle OOP can be done in any language, even assembly. This is because all OO language compilers/assemblers (e.g. C++) ultimately translate the high level constructs of the language into machine language. Thus there is a mapping from an object oriented semantics onto the instruction and data arrays that are executable images.

Here we will present a design and implementation method for producing OO code in the C language. It turns out that using this methodology will strongly improve your overall program design and implementation just as you expect when programming in a native OO language like Java or C++. When working in C, however, the discipline applied to producing good designs comes from the programmer and not from the language itself.

There are substantial benefits to be gotten from learning how to program OO code in C. The biggest benefit for new students is learning much more about how OO is accomplished in languages like Java. Students tend to take too much for granted when they only learn an OO language and never learn the basis for OO constructs like classes and encapsulation, etc. Learning to write classes and instantiating them in C gives the student a peek under the hood that will help them understand just what the object oriented facilities are doing. For example you will see in detail how the new operator works and understand the memory allocation of objects. This insight will help you greatly appreciate just what a language like Java is doing for you (why it is used to code more efficiently) but it will also help you understand many of the pitfalls in languages like Java that a truly knowledgeable programmer should know about.

C and C++ are the languages of choice for systems programming. Knowing how to program in these languages is proving to be a real plus in the job market, even when the prospective job does not involve actually programming in those languages. The reason is that technical employers are well aware that candidates who have mastered C have a much deeper understanding of programming in general and are therefore more likely to succeed in a business that is constantly changing. Grounding in programming basics in C positions someone to learn any new language or paradigm that might emerge in the future.

This document introduces the student to programming OO using C. While it explains the process and methods it will not be a substitute for actual practice. Students should exercise their understanding by writing programs that emphasize object oriented approaches. Some examples will be given below.

Abstract Data Types and Encapsulation

The basis of object orientation derives from the concept of an abstract data type (ADT). An ADT is defined as a (generally complex) data type that can be represented in the computer AND the fundamental operations that are define on that type. A simple example is an integer. An integer is represented by a finite number of bits in a register (of fixed size), say 32 bits wide. It is usually represented using 2's-complement format. An integer is a natural number (or its negation) and the operations of arithmetic are defined on the set. Two integers (in two registers) can be added to produce a third integer within the same size limits. Similarly two integers can be subtracted, one from the other, and so on. We would represent the ADT as:

INTEGER: All natural numbers between 0 and 2n-1-1 and the negations of the non-zero values, 1 to 2n-1, where n is the number of bits wide the register is.

OPERATIONS:

- Complement: invert all bits

- Add: R = A + B; C = carry out

- Negate: Add(Complement(A), 1)

- Sub: R = Add(A, Negate(B))

- Mul: R = (Add(A, A)) (Sub(B, 1) times)*

- Div: R = (Sub(A, A)) (Sub(B, 1) times); R1 = B [where R1 is a second result register, the remainder left in B]

- others

All ADTs are defined in this manner. The descriptions of the operations involve algorithms that take data operands and transform them to results. For example, an operation defined on a data type, FILE would be MERGE (FILE A, FILE B): where a merge algorithm would be specified. Another might be SORT (FILE A): and a composition might be MERGE(SORT(A),SORT(B)).

Classes in an object oriented design are fundamentally ADTs. Classes typically contain data elements and a set of functions (methods in Java) that perform operations on the data.

Structures in C == Classes in Java

In C the complex data construct that allows programmers to define their own data type is the struct. Stuct(ures) are defined as contiguous memory slot that are the size of the sum of sizes of all of the data elements. For example:

typedef struct {

int employee_number;

char * name;

} EmployeeStr;

This struct will define (typedef) a memory map containing four bytes for the employee_number and four bytes for a pointer variable (on a 32-bit machine). The data type is now called an EmployeeStr (where the suffix Str is used to designate that this is a typedef'd struct). As it stands this is equivalent to a class declaration in Java. There are no objects actually allocated in memory. The Java equivalent would be:

class Employee {

private int employee_number;

private String name;

};

The syntax of Java includes access modifiers to establish that only an Employee object can get access to its member variables. This can be handled in C but that is a more advanced version than we need right now.

In the Java version we are taking advantage of the fact that Java has a type of container already defined for string, whereas in C it is necessary to treat strings in a somewhat ad hoc nature. This will not be a real problem however because the standard C library contains many string handling functions that provide the services you would get out of a String class.

Thus far we have only produced a data definition. It should be noted that the class/ADT items above automatically inheret the operations already defined on the designated data elements. So, for example the employee_name item carries with it all of the arithmetic operators we mentioned above. But now we have to define the operations on this more complex data type. These will be compositions of operations defined on each type in the struct/class.

Some basic operations that go with every class definition are things like getters and setters. In C these operations are defined outside of the struct declaration as separate funcitions (but in the same source file). Such as (assume there is an instantiated object of type EmployeeStr):

int Employee_getEmployeeNumber(EmployeePtr employee) {

if ( employee == NULL) return NO_OBJECT_ERROR;

else return employee->employee_number;

}

int Employee_putEmployeeNumber(EmployeePtr employee, int number) {

if ( employee == NULL) return NO_OBJECT_ERROR;

else if (number < 1) return INVALID_EMP_NO_ERROR;

else {

employee->employee_number = number;

return NO_ERROR;

}

}

The prefix “Employee_” for these two functions are not strictly necessary but it helps the programmer to remember that these functions are defined strictly to be used by objects of the type Employee. Note the parameter “EmployeePtr” in both functions. This is a standard mechanism for instantiating specific objects and having the functions operate on the object that calls it. You can have multiple instantiations of the Employee type but the function operates only on the one instantiation that called it and passed it its own referent (see below). That parameter is, in fact, the this pointer that you have been exposed to in Java without probably understanding what it did. It will be explained below. The “Ptr” suffix indicates it is of type pointer to an object of the type of the class (i.e. EmployeeStr).

These examples also demonstrate a primitive kind of error trapping and handling. You will be getting details on more sophisticated approaches later after you have more experience with producing OO designs.

Setters and getters are pretty standard on most ADT/Class definitions. But other operations such as comparing a stored employee name to a test name would be an operation used in, for example, a search through a file of employees for a specific one. The key is to define all understood operations on each ADT as functions. The functions themselves will be implemented in separate object modules (we will talk about module compilation in class) dedicated to a single ADT/class. The object modules are somewhat equivalent to the .class files in Java. When you first start out designing simple programs we will bend this rule a bit, putting everything into one single C source code file (and a header file). When the designs get sufficiently complex we will transition to separate files for each ADT.

Pointers and Memory Allocation of struct == Instantiation of Objects

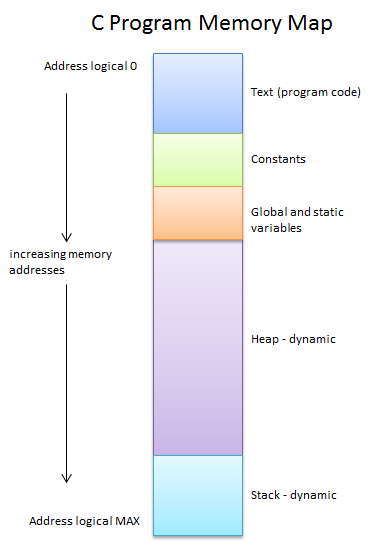

The C memory map is shown in the below figure.

The text (program code) starts at map address 0 (logical). This is execute-only memory. No data can be written to this block once the program starts running. The next block down is the area reserved for constants such as string literals - the strings you explicitly write in your programs. This area of memory is initialized when your program is being loaded and cannot be written to during runtime. Following that is the block for global and static variables. A static variable is one that “belongs” to a specific function. It can only be written to while that function is running. The next block, the big one, is called the heap. This is read-write (dynamic) memory that will change contents during the execution of the program. This is where you will instantiate objects by requesting an allocation of memory that will be reserved specifically for your object. Many objects of the same class can be instantiated here just as in Java. For example, an array of Employee records (one for each employee) would be stored here. The final block is for the stack where function call records are kept. The stack grows down in address space (up from the bottom in the diagram). We will be seeing how the call stack works later. This memory block is also considered dynamic since it changes contents and size during program execution. The division line between the stack and the heap is constantly changing. As the stack grows (up in the diagram) it invades space given to the heap. It can do this without warning unless you explicitly tell the compiler to include stack-checking. The latter is rarely done since in modern memory systems there is more than enough space for both blocks. If you write recursive algorithms, however, it is a good idea to include stack boundary checking just in case.

Objects of type Class (typedef'd struct) are instantiated on the heap using the stdlib function malloc() or one of its family. Recalling the typedef struct...EmployeeStr, from above:

typedef struct {

int employee_number;

char * name;

} EmployeeStr;

we can define a pointer type for this type of structure:

typedef EmployeeStr * EmployeePtr;This pointer type is used to instantiate an instance of EmployeeStr and will become the “this” pointer for all OO function (method) coding. The this pointer is somewhat hidden in Java. You can refer to it inside a method where the assumption is it is the refernce to the specific instance that invokes the method. In C we instantiate an object like this:

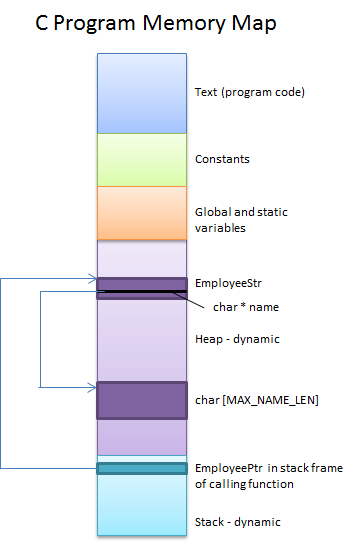

EmployeePtr employee = (EmployeePtr) malloc (sizeof(EmployeeStr));The employee variable is a pointer type to an EmployeeStr that will be created in the heap. malloc() returns a void pointer (one with no specific type) so you need to cast it to the EmployeePrt type for safety. The sizeof built in operator evaluates how many bytes of memory are needed by the EmployeeStr class. In the EmployeeStr definition we need 32 bits (four bytes) for the integer and 32 bits (four bytes) for the pointer to a char (the array of which will be located somewhere entirely differently in memory) on a 32 bit machine. Then malloc() obtains a designated block of memory on the heap of exactly that size from the runtime memory manager and returns the pointer to the start of that allocation. That return value is assigned to the variable employee to be used for dereferencing in the functions. If malloc() fails it returns a NULL value which can be tested to make sure the object was successfully instantiated.

The above code is equivalent to:

private Employee employee = new(Employee);in Java.

Once we have a valid pointer to an object allocated on the heap we can start to use it to store values. In the case of an EmployeeStr object, we can readily store an employee number in the following way:

employee->employee_number = emp_number; // a passed parameter (see below)The value of the integer is stored directly in the object. The name variable, however, requires some additional work. Note that the name variable inside the struct is only a pointer to a char somewhere. So it is first necessary to allocate more memory on the heap to hold a string (char array+1) and then assign the pointer to that additional allocation to the name variable in the struct. We do that like this:

#include <string.h> int size = strlen(name_parameter); char * temp = (char *) malloc (sizeof(char) * size+1)); strcpy (temp, name_parameter); employee->name = temp; // assignment is of pointers not the string itselfThe variable temp is a throwaway. Once the value of the pointer to the allocation is assigned to employee->name there is no need to hang onto temp. When the function terminates the pointer will still be live, but now in the struct. The strcpy() function is necessary to get the char array parameter passed into the function values copied into the heap location. Merely assigning the pointer variables is not sufficient. The pointer points to a location in the heap, but it does not put the string value in the heap itself. The whole setName() function (method) might look like this:

char * setName(EmployeePtr emp, char * name) {

int size = strlen(name);

char * temp = (char *) malloc (sizeof(char) * size+1));

strcpy (temp, name);

emp->name = temp;

return emp->name;

}

This function does not include error trapping and handling! The steps are:

- allocate a block of memory in the heap large enough to hold a name and one byte to hold the null terminator of a string

- copy the contents of the parameter name into the location in the heap

- assign the pointer variable in the instantiated struct the value carried in temp

- return the name pointer for error checking in the calling function

The end condition for these allocations is shown below.

For purposes of completeness and consistency it would have been better to have defined a class called Name and to have written functions (methods) for constructing and destructing both Name and EmployeeStr objects. The complete ADT/Class would look like this:

typedef char * Name; // Name ADT/Class

typedef struct {

int employee_number;

Name name;

} EmployeeStr;

typedef EmployeeStr * EmployeePtr; // Employee ADT/Class

// Prototypes of class functions (methods)

Name nameConstructor(void); // allocates memory in heap and returns pointer to it

int nameDestructor(Name this); // for deallocating memory

Name putName(Name this, char * char_array); // pass a char array and strcpy into the allocation

// pointed to by the this pointer

EmployeePtr employeeConstructor(void); // allocates memory in heap (as shown above)

int employeeInitialize(EmployeePtr this, int emp_no, Name name); // sets employee number and name

// if available

int employeeSetEmployeeNumber (EmployeePtr this, int emp_no); // returns error code

int employeeGetEmployeeNumber (EmployeePtr this, int error); // returns emp number

int employeeSetEmployeeName (EmployeePtr this, Name name); // returns error code

Name employeeGetEmployeeName (EmployeePtr this, int error); // returns name

Module Files and Test Drivers

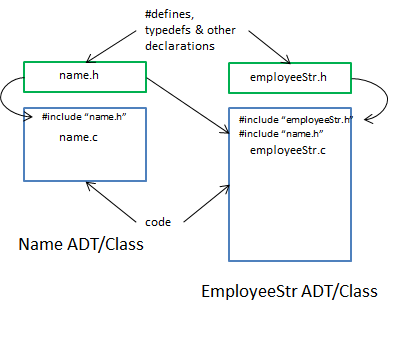

In the above example we might be tempted to develop the code for both the Name and EmployeeStr in a single C file with a single header file. If the Name ADT/Class were only needed in the context of the EmployeeStr then this would be acceptable (as shown above). Name would effectively be an inner class of Employee. But suppose Name objects were used in other contexts as well. The standard practice in C programming is to break programs up into “object” modules with their corresponding .h file headers. Each ADT/Class gets its own .c and .h files and can be compiled seperately to .o files to be linked into other programs as needed.

In the above example Name would be separated from EmployeeStr into two sets of .c/.h files. The name.h file would be #included into the employeeStr.c file so the latter knows what a Name is and can compile correctly. So far this is not much different from .java files and their corresponding .class files. The diagram below shows the relationships between the two modules name.c/.h and employeeStr.c/.h.

This separate module approach does present a small problem but it is solved almost exactly the way it is done in Java. While it is possible to tell the compiler to compile each individual module down to an object (non-executable) file, it remains to test the code to make sure it runs properly. For that you would write a main() function at the bottom of your module .c file. This function would merely test each and every function in the .c file by instantiating an object (running the constructor and initializer) and then sequentially calling each ADT/Class function (methods) and verifying that they work properly. Once a module has been thoroughly tested the main() function is commented out but left in place in case one needs to do more testing or modify the module later.

In the above example the module employeeStr must also use the Name ADT/Class so it would be able to test everything in the nameStr.c code. Here we have two options possible. The first and simplest option would be to #include name.c along with #include name.h (just below the latter). This works and can be used for small modules like name.c but it is not really recommended. For one thing you have to remember to comment out all #include name.c instances in any source modules that used Name. This is a source of compile time error so is generally avoided. The better approach is to use the command line compiler argument for separate compilation. It would look like this:

$ gcc name.c -c name $ gcc name.o employeeStr.c -o empTestOf course you should have commented out the

main() function in name.c before doing this. The compiler will produce an object file with a .o extension for the first compile task. Then this object file will be linked into the empTest executable produced by the second line. There are a number of ways to accomplish this multiple compilation but this will get you started. Eventually we will learn about make files, which are the command line equivalent of projects in an IDE.

Footnotes

* This operation includes an iterative operator that is defined by the hardware seperately.