Seattle used to be know as a nice place, and nice gets on some people's nerves. They think of nice as bland and lacking in edge. Nice people don't blow their noses on the draperies or spit on the floor. They'd rather curl up with their cats, eat vegetarian casseroles and plan organic strategies for eliminating slugs in the garden.

The anti-nice forces should be happy now. Thanks to a much heralded music and drug scene, Seattle has acquired a darker, more angst-filled image. Writer dubbed it "Northwest Noir" in the New York Times.

The phrase sounded great to Seattle and artist Charles Krafft, founder of wht he calls the Mystic Sons of Morris Graves, Seattle Lodge 93.

Like nearly everything Krafft does, the Lodge is a joke he's serious about. He loves Graves, the region's most celebrated eccentric visionary painter, and uses his devotion to ridicule any artist not ing the Graves mode. What's the Graves mode? Krafft will be the judge of that.

Currently, it's noir.

Krafft and his cohorts in the Mystic Sons Lodge put out a call for a "Northwest Noir" show. Of the 40 or so artists who responded, the Lodge selected 35, a half and half mix of Seattle's well known and unknowns.

Anyone who has read this far knows the basis on which the jurors did their minimal pruning. Anything healthy, happy or (shudder) "nice" got the gate.

Remarkably, what's left is a pretty decent show. This town has seen theme shows with big budgets that don't have half the enerty of this no-budget goof effort at the Vox Populi Gallery.

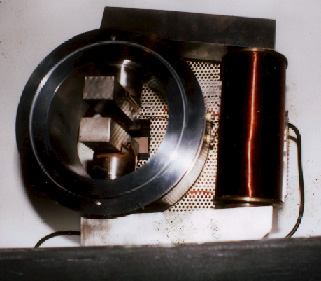

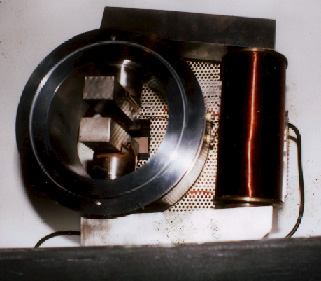

"Seattle Noir" comes with sound effects: a terrible wheezing from a kinetic sculpture by Kurt Geissel and Greg Reeves.

It's matted fur and old feathers are wrapped around a machine shaped like a barbell. Jerking around stage, the piece looks like a spastic bird. If the state were a prize ring, the bird would be down for the count and heading for the hospital. Nature's on life support in "Seattle Noir."

Krafft himself entered the show whith a series of small, brilliantly dumb collages. Krafft photocopied a classic 1948 shot of Graves by the French demi-monde photographer know as Brassai. In one, Krafft pasted the image of a leering and robusly pink baby onto Grave's lap. Like Graves, the kid is smoking.

The work of the late Jay Steensma courtsy his late partner Ree Brown. Both exhibit small paintings of Mount Rainier, Steensma's stark and Brown's wistful. Seensma also has a small landscape, the type for which he is most famous. Seensma rendered the Northwest as a kind of empty badlands, a wash of grays surrounded by thundering silences.

Over Steensma's landscape hangs a half-moon collection of thumb-sized Joe Reno portraits. They are simple yet elegant smears for eyes, nose and mouth.

Laurie Balmuth's paintings featrue blank blondes consorting with the devil. They're done on washing machine lids because the stain on the female character hasn't had a good laundering in the last 700 years.

Piet Mong is the pseudonym of Steve Woods and Tyler Fleeson. They collaborate in marathon painting sessions that Krafft claims involve a lot of talk and no planning. Thsi canvas reveals the three faces of Freud, all beaten down old men, unhappy because the city behind them is in flames.The pair paint in gobs of oil. This painting looks like frosting on a cake, if the cake in question were loaded with explosives.

Loris Graves (pseudonym for Alice Wheeler) photographed a cheery group of plastic deer loaded onto athe back of a pickup truck in Oregon and framed it in thick, plastic logs.

Reese Lamb submitted a dark print of a "negative Space Needle," Seattle's icon just after it turns into a shadow of carbon ash.

When John Staments drove a taxi, he took photos of his passengers. This series from the early '80's is one of his best. Three are here: a natty drunk leaning forward toward the camera, an impoverished senior citizen and a wiped-out family of four on the move to nowhere.

Randy Warren's ink drawing of a couple drilling through a wall has a nasty edge to its ebullient bounce. Doug Parry's painting of a green-faced kid in a baseball cap is both vivid and fragile, as if he painted it in colored smoke.

If the curators were giving a prize for the most chilling image, it would have to go to Jacques Moitoret. His gorgious painting in oil and lacquer shows developer Martin Selig against the backdrop of his building empire. The subject smiles broadly, prince of all he surveys.