Dream Interpretation and False Beliefs

Giuliana A. L. Mazzoni

University of Florence

Pasquale Lombardo

University of Bolgna

Stefano Malvagia

University of Florence

Elizabeth F. Loftus

University of Washington

ABSTRACT

Dream interpretation is a common practice in psychotherapy. In the research

presented in this article, each participant saw a clinician who interpreted a

recent dream report to be a sign that the participant had had a mildly

traumatic experience before age 3 years, such as being lost for an extended

time or feeling abandoned by his or her parents. This dream intervention

caused a majority of participants to become more confident that they had had

such an experience, even though they had previously denied it. These findings

have implications for the use of dream material in clinical settings. In

particular, the findings point to the possibility that dream interpretation

may have unexpected side effects if it leads to beliefs about the past that

may, in fact, be false.

Part of this study was supported by a MURST Grant.

Correspondence may be addressed to Giuliana A. L. Mazzoni, Department of

Psychology, University of Florence, via S Niccolo'89/a, Florence, Italy, 50125.

Received: July 25, 1997

Revised: April 3, 1998

Accepted: April 20, 1998

Dream interpretation is a common current clinical tool used more in some

therapies than in others ( Brenneis, 1997 ). Although this

tool might not necessarily be problematic as an enterprise, what would be the

impact and consequence of a clinician imposing an incorrect interpretation on

dream material? Could sbuch misinterpretation influence patients' beliefs about

their past in ways that might be detrimental? Could patients be led to false

beliefs about their past?

Dream material was viewed by Sigmund Freud (1900/1953 , 1918/1955

) as providing a royal road to the unconscious and as being a vehicle for

unearthing specific traumatic experiences from the past. Psychoanalytic theory

and technique (including dream interpretation) dominated psychotherapy training

well into the 1950s, when behavioral, humanistic, and cognitive approaches,

which do not emphasize dream interpretation, began to have greater impact. Dream

interpretation, or dream work, holds a far less central position among clinical

intervention tools than it did just 30 years ago.

Nonetheless, a sizable percentage of professional psychologists today report

using dream interpretation in their clinical work ( Brenneis, 1997

; Polusny & Follette, 1996 ; Poole,

Lindsay, Memon, & Bull, 1995 ). Moreover, a subset of clinicians who

work in the area of trauma view dreams being "exact replicas" of the

traumatic experiences ( van der Kolk, Britz, Burr, Sherry, &

Hartmann, 1984 , p. 188). For example, one therapist wrote, "Buried

memories of abuse intrude into your consciousness through dreams ... Dreams are

often the first sign of emerging memories" ( Fredrickson,

1992 , p. 44). Another therapist wrote,

Repressed memory dreams are dreams that contain a partial repressed memory or

symbols that provide access to a repressed memory. During sleep, you have a

direct link to your unconscious. Because the channel is open, memory fragments

or symbols from repressed sexual abuse memories often intrude into the dream

state. Even though the memory is embedded in the symbolism of the dream world,

it is possible to use the dream to retrieve the memory. ( Fredrickson,

1992 , p. 125)

Does this sort of clinical dream interpretation actually lead to the recovery

of a genuine traumatic past? Or is it possible that the dream interpretation

might be leading people to develop false beliefs, or even false memories, about

their past? And if so, is it harmful?

We recently published several studies that may have some relevance to these

questions ( Mazzoni & Loftus, 1996 ). We showed that after

a single subtle suggestion, participants falsely recognized items from their

dreams and thought that these items had been presented in a list that they

learned during the waking state. Our participants first learned a key list of

words. In a later session, they received a false suggestion that some items from

their previously reported dreams had been presented on the key list. Finally, in

a third session, they tried to recall the items that had occurred on the initial

key list. A major finding was that participants often falsely recognized their

dream items and thought they had been presented on the key list, sometimes as

often as they accurately recognized true list items. Despite the high rate of

false recognition, and the conviction that participants had about these false

memories, it is reasonable to question whether the same kind of results would

occur with more personally meaningful events.

The Florence False Interpretation Study

We devised a new methodology for exploring whether such activities can lead

people to develop false beliefs about the past. We found individuals who

reported that it was unlikely that they had had certain critical experiences

before the age of 3 years. The age of 3 years is important to shed light on

whether changes that resulted from our manipulation were due to the recovery of

true experiences or the creation of false ones ( Wetzler

& Sweeney, 1986 ). The critical experiences included episodes like being

lost in a public place for some extended time. Later, some of these individuals

went through a 30-min minitherapy simulation with a clinical psychologist, who

interpreted their dream (no matter what the content of the dream) as if it were

indicative of having undergone specific critical experiences in the past.

An initial group of 128 undergraduates from the University of Florence filled

out an instrument that we called the Life Events Inventory (LEI) on which they

reported on the likelihood of various childhood events having happened to them.

The LEI has 36 items, 3 of which are critical items. The inventory asks

participants to consider how certain (confident) they are that each event did or

did not happen to them before the age of 3 years. Participants respond by

ranking items on an 8-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 ( certain it did

not happen ) to 8 ( certain it did happen ). Fifty participants who

had low scores (below 4) on the 3 critical items were selected and asked to

participate in the next phase of the study. The 3 critical items were as

follows: "got lost in a public space," "was abandoned by my

parents," and "found myself lonely and lost in an unfamiliar

place." The cover story associated with the administration of the LEI

explained that the study concerned the frequency of rare and common events that

happened during early childhood and that the study goal was the validation of an

instrument to measure these experiences.

Of the selected 50 participants, half were randomly assigned to a dream

condition, where they received suggestive information about the content of their

dream. The other half did not receive any suggestive information about their

dreams. Of the 25 participants in the dream condition, only 19 completed all

three phases of the experiment; all 25 participants in the non-dream condition

completed the experiment. (The difference in completion rate appeared to be due

to a handful of participants who were randomly assigned to the dream condition

but chose not to participate in what they thought was an additional experiment.

Whether this choice was due to already having sufficient credits or some other

reason was not explored.) The mean age of the final sample of 44 participants

was 21 years, and 64% were women.

All 44 participants returned to take the LEI again after 3 to 4 weeks.

However, those in the dream condition also participated during that time in what

they thought was a completely different experiment but was actually the dream

manipulation.

For the participants in the dream condition, dream interpretation was done

10-15 days after the first LEI. Shortly before the dream session, dream

condition participants received a phone call from a clinician asking for their

participation in a dream and sleep study. Participants were asked to bring in

one or more dreams, which could be a recurrent dream, a recent dream, or a vivid

dream (no constraints were put on the type of dream). These participants had

their dreams individually interpreted by a clinical psychologist. The particular

clinician is a trained clinical psychologist with a private practice in

Florence, Italy. He also is well known in the community from his radio program

on which he gives clinical advice. Moreover, he has a strong, persuasive

personality. In the dream session, the clinician welcomed the participants and

explained that the purpose of the study was to collect meaningful dreams and to

relate those dreams to sleep characteristics. Then the participants read their

own dream report aloud. Next, the clinician asked participants for their own

interpretation of the dream and for their comments on the dream. Then the

clinician offered his own comments. The comments were framed in terms of a

clinical interview (i.e., the psychologist followed a predefined script but was

free to make some modifications depending on the responses of the participant).

Early on, he explained that he had considerable experience in dream

interpretation, and he explained that dreams are meaningful and symbolic

expressions of human concern.

A key feature of the dream manipulation was to suggest to participants that

the dream was the overt manifestation of repressed memories of events that

happened before the age of 3 years. To be specific, the dream interpretation

suggested to the participants that the dream was indicative of a difficult

childhood experience, such as getting lost in a public place, being abandoned by

one's parents, or being lonely and lost in an unfamiliar place-the three

critical items. No matter what the content of their dreams, all participants

received the same suggestion: that one or more of these critical experiences

appeared to have happened to them before the age of 3 years.

To appreciate what the clinician did with the specific dream material, it is

helpful to use a concrete example. Suppose a participant came in with a dream

report about walking up a mountainside alone on a chilly day and commented that

the dream must mean that he finds mountain walking appealing. The clinician

might then discuss part of the dream, mentioning the mountain, that the

participant reported being alone there, and that despite the participant's

remark about liking mountain walking, the "chilly day" suggests that

the experience might be a "cold" one for the participant. At that

point, the clinician would try to induce the participant to agree with this

suggestion. The clinician might then move toward a global interpretation,

suggesting that in his vast experience with dream interpretation, a dream like

this usually means that the participant is not totally happy with himself, he

needs challenge, he resists being helped by others, and he might have social or

interpersonal difficulties. The clinician then might suggest to the participant

that the dream content, and the feelings about that dream, are probably due to

some past experience that the participant might not even remember. The clinician

would then tell the participant that the specific details mentioned are commonly

due to having had certain experiences before age 3, like being lost in a public

place, being abandoned even temporarily by parents, or finding oneself lonely

and lost in an unfamiliar place. Finally, the clinician would ask whether any of

the critical events happened to the participant before the age of 3 years. When

the participant claimed not to remember these experiences, the clinician

explained how childhood experiences are often buried in the unconscious but do

get revealed in dreams.

From this example, it is easy to see some of the general steps that the

clinician followed during dream interpretation:

-

He commented on specific items in the dream and tried to relate those

items to possible feelings that the participant might have. In the example,

the specific items of the mountain walking and the chilly day were related

to the possible feelings about its being a cold experience.

-

He tried to induce the participant to agree with and expand on his

interpretation.

-

He provided a global interpretation of the dream's meaning. In the

example, the clinician suggested that possibly the participant was not

totally happy with himself, needed challenge, resisted help, and so forth.

-

He suggested the possibility that specific events of childhood are

commonly associated with dream reports like the one provided by the

participant. In the example, the specific events were getting lost and

feeling abandoned-in other words, the critical events used in this study for

all participants.

-

He explicitly suggested that such events had happened to the participant,

and he asked for the participant's agreement with that suggestion.

-

When the participant did not recall such an event, the clinician

explained that unpleasant childhood experiences can be buried and remain

unremembered but are often revealed in dreams.

The entire dream session lasted approximately 30 min. At the end of the dream

session, the clinician asked the participant to think over the proposed events

and to return later for the sleep assessment. These participants eventually

returned to participate in a subsequent sleep study that was actually totally

unrelated to the current experiment.

The initial experimenter, who had previously administered the LEI (hereafter

referred to as LEI-1), then contacted the participants in the dream condition

and arranged for them to return for a second administration of the LEI

(hereafter referred to as LEI-2). Approximately 10-15 days passed between LEI-1

and dream interpretation, and an additional 10-15 days passed between dream

interpretation and LEI-2. For the non-dream condition participants, the LEI

administrations were separated by the same amount of time but without any

intervening dream interpretation.

After the LEI-2, participants were thoroughly debriefed. At this time, they

were asked whether they had linked the two experiments in any way, and no

participant reported having done so.

To determine if the false dream interpretation had caused participants to

become more confident that the critical events had occurred, we examined whether

LEI scores moved up or down for each of the three critical items. We also

calculated the percentage of participants whose responses increased, decreased,

or did not change from the LEI-1 to the LEI-2. The data for the three critical

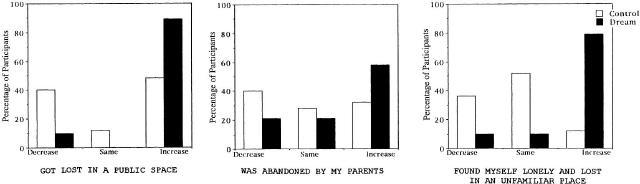

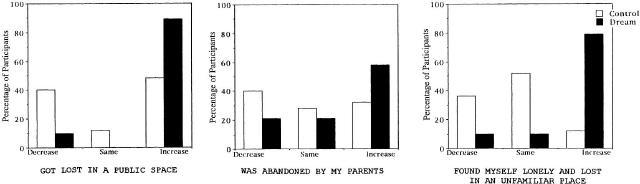

items (lost in public place, abandoned by parents, and lonely and lost) are

shown in Figure 1 . We predicted that after dream

interpretation, participants would be more confident that the events had

happened.

Figure 1. Percentage of participants who decreased, who stayed the same, and

who increased their scores for each of the three critical items on the Life

Events Inventory.

First examine what happened without dream interpretation: These participants

in the control condition reported no change in score on two target items and a

clear decrease on the remaining item ("lonely and lost"). The same was

not true for participants in the dream condition. For all three items, their

scores were far more likely to increase, and they rarely decreased on the LEI-2.

For two of the critical events, about 80% of the scores increased. To analyze

these data statistically, we conducted several Mann-Whitney U tests,

comparing the dream and non-dream (control) conditions. We found that the two

groups differed significantly for two of the critical items: "lost in a

public place" and "lonely and lost in an unfamiliar place."

Participants in the dream condition were far more likely to increase their

confidence that they had had these experiences before the age of 3 years.

The same differences between the dream and non-dream condition groups were

found when we analyzed the degree of movement. For each participant, we

calculated the numerical difference between the scores assigned to each item in

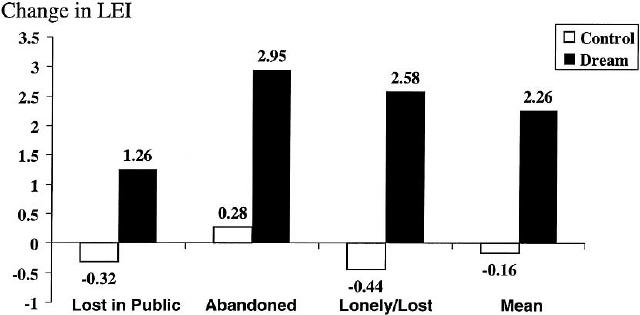

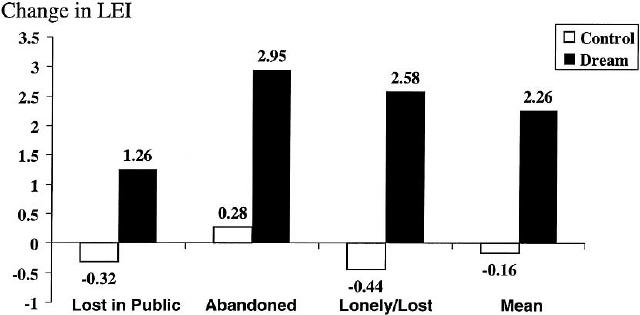

LEI-2 and the scores assigned to the same items in LEI-1. Figure

2 shows the change scores from LEI-1 to LEI-2 for the three critical items

for non-dream condition versus dream condition participants.

Figure 2. Mean change in scores on the Life Events Inventory (LEI) for each

of the three critical items. At the right is mean change collapsed across the

three critical items.

As Figure 2 shows, for control condition participants,

the changes in LEI scores were relatively small and not systematic. One item

changed in a slightly positive way ("abandoned by parents"), whereas

the other two items changed in a slightly negative way.

For the dream condition participants, the picture was completely different.

All three items changed in a positive direction. The biggest difference between

dream and non-dream condition participants occurred for the item "lonely

and lost in an unfamiliar place," where the dream condition participants

showed a mean positive change of 2.58 and the control participants showed a mean

negative change of -.44. At the right of Figure 2 , the mean

change in LEI is averaged across all critical items and participants, and a

strong overall influence of the dream interpretation can be seen. The mean

change in the dream condition was 2.26 on the 8-point scale, whereas in the

non-dream condition it was -.16.

To analyze these data statistically, we conducted several students' t tests

for independent samples on the change scores. We found that the dream and

non-dream condition participants differed significantly for two critical items:

lost in a public place and lonely and lost. Dream and non-dream participants

differed on the last critical item, abandoned by parents, only by a one-tailed

test. Thus, the two methods of analysis, one that involved proportions of

participants who shifted and one that involved measures of mean shift, produced

similar results.

To be sure that our results were not due to inadvertent differences in

pretreatment LEI scores, we calculated the mean pretreatment score for each

critical item. These pretreatment scores are shown in Table 1 ,

separately for dream and non-dream participants. The posttreatment mean scores

are also shown. Notice that the dream and non-dream participants did not differ

in terms of their pretreatment scores, but they showed large differences in

their posttreatment scores.

The previous two analyses suggested that the dream manipulation caused

participants to become more certain that they had had specific negative

experiences in their early childhood. A question then arose as to whether the

shifts were localized only to the specific experiences mentioned by the

clinician, or whether the clinician's intervention caused a general negative

feeling, creating in participants the belief that they were more likely to have

experienced a vast array of negative events in their early lives. We assessed

this possibility by examining the dream condition versus non-dream condition

differences on the negative filler items, such as "witnessed a person

dying" or "threatened by a stranger." If the dream manipulation

produced general negativity, this negativity might be represented in increased

confidence on negative filler items as compared with non-dream condition

responses on those negative filler items. In fact, we found that the dream

manipulation had no impact on the negative filler items. Rather, the influence

of the dream manipulation was very specific to the critical items that were

specifically mentioned by the clinician.

Why did the dream interpretation lead to increased confidence that certain

suggested events occurred? One possible explanation is that the dream

interpretation created a true belief, reminding some participants of a true

experience from their past. Such a reminder, if it occurred, probably did not

occur during the therapy session itself, because no participant reported a

memory for one of the critical events during the therapy. However, in the 10-15

days between the therapy and the final session, some participants might have

recalled an actual experience. We deliberately suggested critical events to have

occurred before the age of 3 years so that any memory that was produced could be

deemed unlikely to be a real memory because of the childhood amnesia problem.

However, it is entirely possible that the therapy might have led to ruminations

that reminded participants of an event that occurred after the age of 3 years,

but they misdated the experience during LEI-2 and mistakenly thought that it

occurred before the age of 3. This process would lead to dramatic shifts in the

LEI. Our data cannot rule this possibility out completely, and it is possible

that these kinds of cases accounted for some of the shift that we observed.

However, we would argue that if participants were so ready to conclude after

dream interpretation that an experience that they actually had at age 6 or 8 or

12 happened to them before the age of 3, this also would constitute a distortion

of belief or memory.

Another possible reason that participants increased their confidence in the

suggested events is that the dream interpretation created a false belief. If

false beliefs have been constructed, how and why does this process happen? One

answer to this question can be found in the large literature on memory

distortion that has shown that people are susceptible to suggestion ( Gheorghiu,

Netter, Eysenck, & Rosenthal, 1989 ). In the current empirical work, we

have found a form of suggestion that is both explicit and subtle. It is explicit

in that the clinician used his authority to tell the dreamers that their mental

products were likely to be revealing particular past experiences. It is subtle

in the sense that the dreamers were encouraged to come up with their own

specific instances of such experiences.

Implications and Applications

Our findings have important implications for therapists. They show that

people are suggestible in a simulation that bears more resemblance to a

therapeutic setting than has been used in prior empirical studies. Moreover, the

findings hint at the strong influence that a clinician can have in a short

period of time. This power may extend to other therapist-client interactions

that are characterized by therapist interpretation of information provided by

the client.

One might ask whether it is reasonable to generalize from our brief therapy

simulation with students to the world of clinicians and their patients. After

all, many of the differences between our minitherapy and real-world therapy are

relatively easy to point out. Nonetheless, we believe that these very

differences are such that we may be underestimating the power and influence that

can occur in a clinical setting. We used students, who were presumably

reasonably mentally healthy, whereas clinical patients may have a greater need

to find an explanation for problems or distress. We had a single short therapy

simulation, whereas clinical patients often experience many sessions during

which suggested interpretations are offered to them. Our therapy simulation was

limited to only a few elements that the participants provided (e.g., the dream

and a brief reaction to the dream), whereas clinical patients provide a great

many elements (dreams, thoughts, behaviors, feelings) with which the therapist

works. Whether these elements are critical for influencing how people reflect on

their past experiences is, of course, a matter for further research

investigation.

One might ask whether it is even the case that therapists are using dream

material to suggest that events occurred in a client's early life. We have found

a number of examples that support the contention that some therapists do indeed

make these kinds of suggestions from dream material. This conclusion comes not

only from surveys of clinicians (e.g., Poole et al., 1995 ),

but also from the writings of specific clinicians. For example, in Crisis

Dreaming, readers are told, "Recurring dreams, particularly of being

chased or attacked, suggest that such events really occurred" ( Cartwright

& Lamberg, 1992 , p. 185). Are the authors of this book communicating

this information to their clients? Are therapist-readers of this book taking

dream material that involves chases and attacks and telling a client that it

means that such events occurred? Although we cannot know that therapist-readers

are following the advice implicit in this book, it is worth considering the

likelihood that they might do so and might inadvertently create false beliefs or

memories.

Could therapists produce similar effects without explicit dream

interpretation? We believe the dream interpretation is probably not necessary

but might add a bit of influential power. Here is why: Suppose instead of

interpreting dreams the clinician simply responds to the comments made by a

client during the first 5 min of interaction. If the clinician takes that 5 min

of material and interprets the material as being indicative of an early

childhood trauma, the client may eventually come to believe that he or she

experienced such a trauma. In fact, even in the absence of dream interpretation,

such suggestive comments might increase the likelihood of illusory beliefs or

memories. According to Lindsay and Read (1995) , suggestions

from a trusted authority can be especially influential when they communicate a

rationale for the plausibility of buried memories of childhood trauma. Moreover,

the trusted authority might be especially influential if he or she offers

repeated suggestions, giving anecdotes ostensibly from other patients.

However, it is also worth pointing out that working with dream material might

be a particularly potent way to influence clients, for better or worse. It

certainly might help to enhance the influence process, because people presumably

enter therapy with a set of beliefs about the meaning of dreams in their lives

and how much dreams can reveal about an individual's past. Given a

predisposition on the part of some clients to already believe in the

significance of dreams, the trusted authority can capitalize on the a priori

beliefs and use them in the service of altering the autobiography.

Are therapists aware of the power they have? Almost by definition therapists

must believe that they have the power to change people, because at least some

forms of therapy emphasize changing people's beliefs from ones that are

nonadaptive to ones that are more adaptive. Even more generally, therapy is

about changing people. However, therapists may be appreciating their power to

change people primarily when they are thinking about the good it can produce in

people or thinking about ways to make their clients change for the better. They

may not be appreciating that they also have the power to change people for the

worse. This type of change can happen, for example, when a therapist adopts a

hypothesis too early and, even when the hypothesis is wrong, presses it on the

client. Our data show that even a randomly generated hypothesis can be embraced

by individuals and can produce profound changes in the way they view their past.

We have demonstrated that these interventions can make people believe that they

have had experiences that they previously denied. However, it is also likely

that these interventions have the power to make people doubt their true

experiences. Our hope is that heightened awareness of this power might enhance

the likelihood of cautious use of these sorts of interventions.

References

Brenneis,C. B. (1997). Recovered memories of trauma:

Transferring the present to the past. Madison, WI: International

Universities Press.

Cartwright,R. & Lamberg,L. (1992). Crisis dreaming-Using

your dreams to solve your problems. New York: HarperCollins.

Fredrickson,R. (1992). Repressed memories. New York:

Simon & Schuster.

Freud,S. (1953). The interpretation of dreams (Standard

ed. 4 & 5). London: Hogarth Press. (Original work published 1900)

Freud,S. (1955). From the history of an infantile neurosis (standard

ed. 17, pp. 1-122). London: Hogarth Press. (Original work published 1918)

Gheorghiu,V. A., Netter,P., Eysenck,H. J. & Rosenthal,R.

(1989). Suggestion and suggestibility. New York: Springer-Verlag.

Lindsay,D. S. & Read,J. D. (1995). "Memory work"

and recovered memories of childhood sexual abuse: Scientific evidence and

public, professional, and personal issues. Psychology, Public Policy, &

the Law, 1 846-908.

Mazzoni,G. A. L. & Loftus,E. F. (1996). When dreams become

reality. Consciousness & Cognition, 5 442-462.

Polusny,M. A. & Follette,V. M. (1996). Remembering

childhood sexual abuse. , 27 41-52.

Poole,D. A., Lindsay,D. S., Memon,A. & Bull,R. (1995).

Psychotherapy and the recovery of memories of childhood sexual abuse: U.S. and

British practitioners' opinions, practices, and experiences. Journal of

Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 63 426-437.

van der Kolk,B., Britz,R., Burr,W., Sherry,S. & Hartmann,E.

(1984). Nightmares and trauma: A comparison of nightmares after combat with

life-long nightmares in veterans. , 141 187-190.

Wetzler,S. E. & Sweeney,J. A. (1986). Childhood amnesia:

An empirical demonstration. In D. C. Rubin (Ed.), Autobiographical memory (pp.

191-201). Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Back to

Elizabeth Loftus homepage

|